The origins of baklava are uncertain. Its history is not at all well documented. Some ancient Greek desserts included in the famed Deipnosophistae (“The Dinner Experts,” a 3rd-century-BC Greek text featuring classical recipes) might resemble baklava insofar as they’re filled with nuts and honey, but lack the characteristic flakey dough. In its current form, food historians agree, baklava was most likely developed in the imperial kitchens of the Topkapi Palace in Constantinople – modern Istanbul. It is known that the Sultan presented trays of baklava to his Janissaries every 15th of the month of Ramadan, in a ceremonial procession.

Baklava’s arrival in Greece can be traced back to these imperial times. As the empire expanded its influence across the Middle East, the Balkans, and the Mediterranean, it brought with it the culinary traditions of the many territories it had already conquered, its imperial kitchens included. Baklava quickly became a popular sweet treat among both the royalty and commoners.

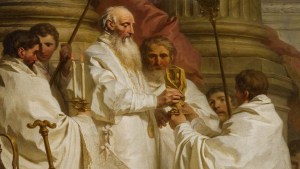

The Ottomans ruled over Greece for centuries, introducing their culinary traditions, baklava included, to the region. As the Ottoman Empire reached its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries, baklava had firmly established itself in Greek cuisine. But then, the Greek gave it a particular twist – perhaps as a form of religious and cultural resistance.

Typically, baklava is made with at least four layers of phyllo dough and two to three layers of nuts and syrup. Some more elaborate recipes call for up to 12 layers of phyllo dough and five or more layers of nuts and syrup. But Greek bakers and households make it with 33 dough layers, referring to the years of Jesus’ life.

Surely there are more changes to the traditional baklava recipe, incorporating local ingredients and regional variations. Today, Greek baklava is recognized for its use of honey and cinnamon, and a variety of nuts, such as walnuts and pistachios – butmainly because of its religious symbolism.