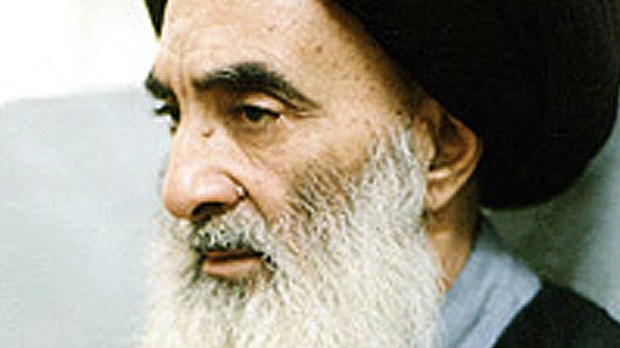

Pope Francis is scheduled to meet on March 6 with Iraq’s highest Shiite authority, Ayatollah al-Sistani. Fr. Christopher Clohessy is a doctor at the Pontifical Institute for Arab Studies and Islamology (PISAI). An eminent specialist* in Shiite Islam, this South African researcher deciphers the issues at stake in this historic meeting.

What does Grand Ayatollah al-Sistani mean for the Muslim world?

He’s an essential figure in Shiite Islam. At the head of the Najaf school, he has under his authority a very large number of Shiite scholars scattered throughout the world. Like Pope Francis, he’s an attractive figure. His popularity around the world, including in Iran—the country where he was born—shows that many people prefer his perspective, which is slightly more moderate than that of Rouhollah Khomeini [the Ayatollah who came to power in Iran in 1979 and died in 1989, Ed.]. That political thought, still at work today in the Islamic Republic of Iran, holds that all powers should be concentrated in the hands of clerics.

A disciple of his former professor the Grand Ayatollah al-Khoei (1899-1992), al-Sistani has been in the top 10 positions of “The Muslim 500,” the ranking of the most influential Muslims in the world, since 2009. In 2005, he was also ranked among the 100 greatest intellectuals in the world. In 2014, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

What is his authority in Iraq?

He’s one of the most influential men in the country. He played a very important role as a peacemaker and treaty negotiator in religious and political affairs after the American invasion in 2003. Urging the clergy to engage in justice and politics to better guide the Iraqi people, he called for a democratic vote to form a transitional government, and encouraged the people to participate in the crucial January 2005 elections—including women, whom he invited to mobilize in a special fatwa. He pleaded with Iraqi Shiites not to respond to attacks by Sunni extremists. Calling for calm after a series of bombings, he often explained to the Shiites that the culprits were not their Sunni neighbors, but the extremists. In 2014, he also called on Iraqis to support their government in the fight against the organization Islamic State.

Is the meeting to be held between the pope and the Shiite leader the counterpart of the meeting between the pope and the Sunni al-Tayyef?

The meeting with the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar was important. But I believe that, for Shiite Islam, this meeting with Pope Francis is fundamental because it means that the whole family of Islam is now considered. Even though Shia Islam has become a minority, it still represents millions of people around the world. Through this meeting, the pope is sending a message to the Shiites to tell them that they are not forgotten or obsolete. He’s assuring them that they’re an integral part of the process of dialogue and peace in the world.

As you said, al-Sistani represents a slightly different Shiite current from Khomeini and the school in Qom, Iran. How will Iran react to the pope’s visit to al-Sistani?

Iran should not react negatively. In Qom itself, where al-Sistani first studied, he’s highly respected. Admittedly, his vision of Islam differs slightly from Khomeini’s. But despite some disagreements with the clerics in power in Iran, al-Sistani has never really encouraged rivalry between the two major Shiite centers. I think the meeting will be almost unanimously welcomed by Shiite Muslims.

What could be the concrete impact of such a meeting?

I don’t expect a document to be signed as was the case with the pope and the Grand Imam of al-Azhar and the document on the Human Brotherhood. I don’t think al-Sistani could sign a document just for the pleasure of it or for the symbolic value. The meeting—which will be short—is part of a larger agenda. Later, there could be a joint declaration from Najaf and the Vatican.

However, this is a highly symbolic meeting, and sometimes the symbolic content is more important than what is said. In spite of the criticism, sometimes violent, that can be observed on the social networks between the so-called “liberals” and “conservatives”—on both the Catholic and the Shiite sides—I would say that Francis and al-Sistani share very similar visions and perspectives. Both want to show that they know the value of peace and that they’re willing to work hard for it.

How are the pope and the Church perceived in the Shia world?

I’m not sure whether the pope, by virtue of his office and mandate, or the Catholic Church, a global institution, are high on the radar of Shia Islam. Nevertheless, Pope Francis is a popular figure, partly because of his name. In Islam, the story of St. Francis’ encounter with the Sultan is still remembered. St. Francis is considered throughout the world as a man of peace. So Pope Francis is seen in this light.

Where are the relations between Shiites and Catholics today?

In recent decades, there’s been a growing dialogue between Catholicism and Shiism—there are close theological and spiritual links between the two religions. Since the declaration Nostra Aetate and the Second Vatican Council, Islam has been in regular dialogue with the Catholic Church, but less so with the other branches of Christianity. In my opinion, as Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI says, this dialogue has been and continues to be crucial, but it’s difficult to call it “theological.” Indeed, apart from informing one’s partner about one’s own beliefs or asking questions about their belief system, it’s unlikely that these exchanges will go any further, or that fundamental doctrinal and theological positions would be likely to evolve or be compromised.

What could come out of the conversation?

Often these dialogues are little more than a group of Muslims inviting a group of Christians to explain complex Christian doctrines such as the Trinity or the Incarnation.

However, as Benedict XVI explained, we must continue to try to encourage frank exchanges on central themes, such as freedom of worship, human dignity or non-violence.

Also, one certainly cannot deny the potential of Islam as an ally in the defense of the great religious values of faith and obedience to God. Christianity and Islam are actually on the same side in a battle against radical secularism.

Between the Shiites and the Sunnis, with whom does the Catholic Church have the easiest dialogue?

In my opinion, there are stronger ties between Catholics and Shiites than between Catholics and Sunnis. This is partly due to the commonalities that exist between Shiites and Catholics: for example, a common belief in the intercession of the saints, important parallels between al-Husayn, the great martyr of Shiism, and Jesus; between Fatima [the daughter of the prophet Muhammad, Ed.], the suffering and virgin mother of al-Husayn, and the Virgin Mary. In addition, both religious systems attach great importance to rituals and the need to remember. Ritually, memory is used to make the event present and to place the believer at the heart of the event.

Although bridges can exist between Catholics and Shiites, it is nevertheless noted that the situation of Christians in countries with a Shiite majority is not very encouraging.

That’s right. There’s no doubt that Christian minorities in Muslim countries do not enjoy full rights. During his trip, it seems to me that it’s essential that Francis not only speak to the Christians of Iraq, but that he also have the courage to challenge the authorities on the subject of religious freedom. The Document on Human Fraternity will remain a worthless piece of paper if it doesn’t help to bear real and concrete fruit. This has not yet happened.

Interview by Hugues Lefèvre

*Father Christopher Clohessy is the author of several reference books: Fâṭima, Daughter of Muḥammad (2009, 2018 2ND ed.), Half of My Heart. The Narratives of Zaynab, Daughter of ʻAlî (2018), and Angels Hastening. The Karbalā’ Dreams (2021), all published by Gorgias Press. In February 2021, he was awarded the 28th International Book Prize of the Islamic Republic of Iran. He received a prize in the category of Distinguished Researcher.